The internet has changed the world in myriad ways. It’s changed how people relate to each other, changed the stories they tell about themselves and the way in which they tell them. One of its most notable effects is that it has enabled people to participate creatively in the pop-mythology narratives that they partake of, rather than merely being passive observers. This has allowed the creation of communities that, if they possibly could have existed before the advent of the digital world, would have been much smaller and much less apparent to anyone not in them. In the past decade, Twilight and Harry Potter have probably provided the most visible examples of such communities in the West. There is an enormous outpouring of creative works affiliated with both of these series on the web, things like fanfiction, fanart, and cosplay. Some people have come to define themselves by their participation in such communities, and many fledgling artists begin their careers by producing works that are part of them.

As huge as both Harry Potter and Twilight have become, there is a series in Japan that eclipses them both in terms of creative fan output, so much so that it seems it should be considered as a different kind of phenomenon, almost a kind of cult or religion instead of a cultural fad. That series is Touhou Project.

“Touhou” literally means “the East,” or “Eastern.” It’s difficult to define what Touhou is in a brief statement. What it began as was a series of top-down shooting games set in the fictional land of Gensokyo, a sort of spiritual echo of Japan’s agrarian past. Gensokyo is populated by a pantheon of supernatural beings, ranging from shrine maidens and witches to demons, ghosts and goddesses. It was dreamed up by a man named Jun’ya Ota, a reclusive figure who doesn’t give many interviews and is best known among fans for his oft-professed love of alcohol.

Ota, more commonly known by his creative pseudonym, “ZUN,” began making Touhou Project games in 1996 when he was a member of a video game development club at Tokyo Denki University. He’s been quoted as saying that the reason he started creating games was because didn’t like the games that other people were making and wanted to see what he could do himself. The first game he made, Highly Responsive to Prayers, was programmed for the PC-98 home computer platform and was a relatively simplistic block-breaking action puzzle game in which the player controlled a Shinto shrine maiden named Hakurei Reimu. Ota proceeded to make four more games in the series during the next two years, all of them top-down shooters featuring Reimu and other characters. However, the PC-98 was dying as a platform at the time, and Ota’s personal game creations were more of a hobby than a vocation. After releasing the fifth game at the end of 1998, he abandoned the series and started working on games professionally for Taito. Then, in 2002, Ota finally released another Touhou Project game, this time for Microsoft Windows. The game was called the Embodiment of Scarlet Devil.

For most people, this is where the Touhou phenomenon began. Scarlet Devil looks crude by today’s standards, with primitive 3D backgrounds and very simple sprites, but there’s an eccentric charm to it that’s immediately apparent upon booting up the game. After a loading screen featuring rather precious Engrish (“Girls do their best now and are preparing. Please watch warmly until it is ready.”), the player is greeted by a misty, shadowed picture of Reimu sitting against a wall, wearing an outfit that looks like a frilly Gothic Lolita version of a shrine maiden’s costume. Her appearance is doll-like, and the amateur nature of the artwork makes it hard to tell how intentional that is. The delicate, tentative music playing in the background somehow makes the whole scene work, though. One feels as if they are entering a realm of mysterious and hidden history, something like exploring an antique shop in a foreign country. It’s a very unusual sensation to have during the intro of a computer game based around dodging bullets and shooting things, and it’s a perfect example of why Touhou has become the phenomenon that it has. Ota is enormously talented at evoking atmosphere through the combination of visuals and music, and the content of the Touhou series typically resembles ballet and opera as much it does a standard arcade shooting game; the refined and intentionally spiritual nature of his dreamscapes contrasts with the frenetic content of the gameplay to create an experience that often approaches the sublime, and sometimes reaches it.

As for the gameplay, the fine details aren’t particularly important; the player shoots down enemies (many little fairies and occasional abstract shapes), collects power-ups and bombs, and attempts to get a high score while dying as seldom as possible. This is all standard shooter fare, but it should be noted that Ota does it quite well, with intricate point systems that vary by game and a large variety of player character options. The difference from more mundane games lies in how Ota crafts his scenes: everything is cued with the music, waves of enemies and boss characters arriving at just the right moment. As the games progress, the patterns of bullets that the player character must make her way through become increasingly elaborate. Often they are stunningly beautiful, even mesmerizing: neon explosions that form shifting star flowers and digital mandalas. These too go along with the music, to the extent that they almost seem to become the notes. The thing that makes all this truly wonderful, however, is its participatory nature. Rather than being a mere observer of the spectacle, the player must dance along with it, weaving through the patterns and becoming one with them. The games are often very difficult, and improving one’s gameplay is like learning to play a piece of music. The patterns are always the same, so all the player has to do is practice. Completing some of the harder patterns can be extremely gratifying, and the intensity of the concentration that is required combined with the hypnotic beauty of the swirling patterns can create a strangely transcendental experience, one that feels almost inappropriate coming from a video game.

None of this would work as well as it does if the music it was set to wasn’t memorable. But it is, extremely so. Ota began writing songs when he was in junior high, and musical composition may be his greatest creative talent. His style is difficult to pin down to a genre; he is fond of elaborate arrangements that are nearly impossible for a person to play at full speed, of intricate piano lines that fit together like the teeth of combs, and of gradiated arcs of rainbow pitch that swirl around his melodies. For instrumentation, he keeps it light and simple: mostly synthetic pianos, strings and brass instruments. Much of his work has an airy, ethereal quality to it because of this, and a feeling of detached elegance. The most important thing, though, is that Ota is incredibly competent at writing catchy melodies. It’s a talent that has made him one of the most-covered musicians of all time.

That probably sounds like a dubious statement, but the fact is that there are over five thousand albums published by groups covering Ota’s music, and countless more cover songs that have not been officially released. His songs have been reinterpreted in genres as diverse as classical, electronic, jazz, and heavy metal, often with impressive results. The Touhou music scene is so vast that some of these works become memes in their own right, and occasionally they pop into the American cultural consciousness. The stylish shadow-art video for “Bad Apple,” an electronic dance cover of a song Ota wrote for one of the PC-98 games, managed to make its way onto a viral media segment on CNN. American Touhou fans were outraged that CNN got most of its information wrong in the segment, and someone reposted the video on youtube with a disparaging overlay: “Cirno News Network.”

Here we come to one of the other primary reasons for Touhou’s popularity. Ota’s greatest talent may lie in his music, but he also has a knack for creating stylish characters that are archetypal while still seeming unique. Cirno, for example, is an ice fairy who first appeared in Scarlet Devil as the whimsical guardian of a frozen lake. She reappeared in the next game, Perfect Cherry Blossom, and two years later her popularity exploded when Ota included a small notation in an instruction manual for another game, Phantasmagoria of Flower View. Various items on a screenshot of the game were marked with circled numbers, Cirno being marked with the number nine, which in the key was jokingly notated as “idiot.” This is a pretty good example of how fans hang on Ota’s every word, as “circle nine” and the idea of Cirno being a fool instantly became a meme, spawning countless pieces of fanart, songs, flash videos, and other parodies.

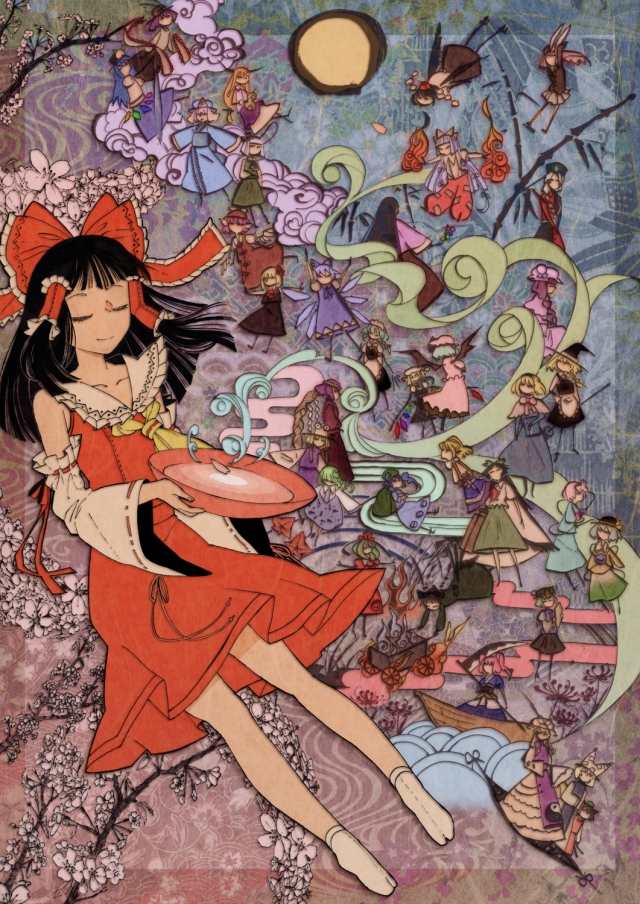

This fanaticism isn’t baseless. Much like how the games wouldn’t work if the music wasn’t any good, a character like Cirno wouldn’t be so popular if there wasn’t something there to draw interest in the first place. While Ota is a notoriously unskilled at drawing the human figure, nearly incapable of drawing hands or even natural-looking arms and legs, he makes up for it with a keen eye for fashion. Cirno is a light-blue-haired girl with a big blue bow on her head, poofy white sleeves, and a cerulean dress with a zigzagging white pattern at the bottom. She has wings, made of huge transparent ice crystals that seem to float independently behind her. It’s a simple, attractive design, easy to recreate and fundamental enough to allow for many stylistic variations, and it seems likely that Ota’s inability to draw his own characters well is one of the things that spurs so many people to re-draw them for him, to bring out the full potential of his ideas. On the online Japanese artist community Pixiv, there are over seventy-five thousand pictures featuring Cirno. All in all, Pixiv has over one million Touhou images. To put that in perspective, deviantART, the American equivalent of Pixiv, has about nine hundred thousand images for Twilight and Harry Potter combined. It would take a person months, if not years, to see all of these Touhou pictures, and in the meantime thousands more would be produced. The rate at which fans create these works seems to be growing, too. There were roughly forty thousand Touhou pictures posted on Pixiv in October of 2011 alone.

Even more remarkable than this is the semi-professional doujin scene, the core of the Touhou fandom. “Doujin” means a group of people who share a hobby or an interest. The word is often translated in English as “circle,” and usually refers to communities of artists who create comics, music or games that are self-published in small print runs. Such items are referred to as “doujinshi.” Touhou itself is a doujin game series, and Ota originally distributed his games at Comic Market, Japan’s enormous biannual doujin meetup in Tokyo. At the December Comic Market in 2003, after Ota released Perfect Cherry Blossom, there were seven circles selling Touhou doujinshi. By 2008, that number had grown to 885 circles. In 2004, Ota started his own Touhou-centric doujin gathering called Reitaisai. It had 114 participating circles in that year, and in 2011 it had approximately 4,940 circles. This is where all of those CDs from bands covering Ota’s music come from, and it’s also the source of thousands of comics and dozens of fan-made games.

This massive quantity of for-sale derivative works may come as a surprise. Selling works based on other artists’ material is basically unheard of in the West, but it’s actually a common thing in Japan. There seems to be an unspoken rule that as long as the fan productions are small-scale and independently financed, they’re ok. The most unexpected thing about the Touhou doujin scene, however, is how high the production values generally are. Touhou doujinshi comics are usually printed with dense glossy covers, some of them embossed with holograms, and the interior pages are often thick and expensively printed, looking much more professional than what you would see in a Western fanzine comic book. Many of these doujinshi creators make no profit on their works, breaking even at best because of the high production costs. It’s a labor of love, and it’s rather astonishing that so many people participate in it.

There is a definite danger of Touhou becoming commercialized, though, and Ota has fought a continuous battle against that possibility. In the past two years, people have begun to produce anime works based on the games, and Touhou goods like figures and models have become more and more common. Ota has forbidden the games to be ported to cellphones, and demands that people selling derivative works limit their channels of distribution to doujin events and small stores where such items are typically sold. Mostly, he just requires that people give him credit for the characters and music that he creates, which seems amazingly generous considering the mind-boggling amount of things being sold that are based on his art. ZUN could probably be a millionaire if he wanted to, but he seems content to be a sort of patron saint of independent artists.

One has to wonder, though, why Touhou has become such an incredible hit; why it has come to define the doujin community in the way that it has. Ota is an amazing auteur, and Japan’s particular attitude towards fan-made works is conducive to the phenomenon surrounding his art, but he is only one man in a country full of talented creators, and his skill alone can’t explain why so many people’s imaginations have been captured by Touhou.

The real reason for the phenomenon may be that Touhou constitutes something of a modern Japanese mythology. Gensokyo is transparently representative of pre-industrial Japan, a world in which mystery and magic still existed, and Ota has said directly in supplementary materials that it was “sealed off from an increasingly scientific and skeptical world in 1884.” The guardian of the border between Gensokyo and the modern world is Hakurei Reimu, the anchoring character of the series who tends a simple Shinto shrine at the place where the two realities meet, and on whom the task falls to re-balance the world when things go wrong. The games always start with the premise that something has upset the natural order in Gensokyo. In Embodiment of Scarlet Devil, a red mist covers the land and Reimu, along with the Occidental witch Marisa Kirisame, go to discover what has caused it. In Perfect Cherry Blossom, Spring fails to come to Gensokyo and the two set out again to discover why, along with an erstwhile antagonist from the previous game. In Imperishable Night, there is a night that seems will never end, and once again the heroes seek out the reason for the disturbance. While on these journeys, they invariably encounter a cast of demure supernatural creatures, all of them female, who engage the protagonists in humorously combative conversations before launching into their personal bullet-ballet sequences.

Invariably, the cause of the disturbance in Gensokyo is something benign, like a diminutive vampire who wanted to make it dark so she could enjoy drinking her tea outside, or a ghost who stole the Spring because she was using it to grow a gigantic cherry tree. Rather than striving to change the world, Reimu and the other protagonists spend their time addressing such incidents to keep the natural order in place. When they’re not resolving these issues, they are portrayed as having idyllic, pastoral lives; living easily in a world that largely takes care of itself.

This reverence for the cycles of the nature most likely comes from Ota’s childhood. He was raised in a small mountain town, far away from the bustle of modern cities, and has said on his blog that growing up in such a place gave him a lot of inspiration in life, even if it was a little lonely. It’s easy to see how isolation combined with immersion in untouched rural beauty could be the catalyst for Gensokyo, with its near-fantastical nature scenes and its population of friendly supernatural women. It as if Ota took the world he knew as a child and filled it with a collection of imaginary friends, some of whom seem to be directly inspired by one of his other main influences, Agatha Christie. One of the most popular Touhou characters, a puppeteer magician named Alice Margatroid, is clearly named after Miss Murgatroyd, a character from Christie’s A Murder is Announced. The refined, subtle nature of the conversations between Ota’s characters seems to show Christie’s influence as well.

For the most part, though, Ota’s influences are of the East, and his games sometimes contain direct references to real places in Japan. The tenth game in the Touhou series, Mountain of Faith, is a love letter to the Grand Suwa Shrine, a 1,200-year-old Shinto temple close to a lake and the mountain of the title. The enemy characters in this game are two Autumn spirits, a curse-goddess, a kappa, a mountain tengu, and ultimately a rival shrine maiden and her patron gods. It doesn’t get much more Japanese than this. Fans of the series adore the cultural tributes, going so far as to make pilgrimages to the actual shrine, and they leave prayer plaques there, decorated with art depicting the fictional shrine maiden and her deities. Although this is not the first time that Japanese fans have made media-related shrine pilgrimages, the Touhou ones have occurred on a massive scale. One American visitor remarked that there were too many Touhou plaques at Suwa for him to photograph.

Shinto is an animistic religion with the idea that everything in the natural world contains spirits, and that concept seems very close to the essence of Touhou itself. The characters, even the mortals like Reimu, are heavily archetypal, and they seem to exist as ideas or modes of being as much as they do as defined individuals. In the games, we come to know them only through their character designs, their bullet patterns, and some sparse dialogue, most of which is humorous in tone. Ota sketches them out a bit more in supplementary materials, but the information he provides is mostly trivia, small facts about their personal tastes and habits. The way he describes his characters is often whimsical; he has a tone of open-ended exploration and imagination rather than one of authorial finality, and he’d rather tell you an amusing anecdote than give you the lowdown on what everything is really about. Ota seems content to dream up these characters and then set them free into the vast world that exists in the imaginations of the fandom, where they invariably mutate. Many of the characters have taken on significance that he never intended in the first place. Kaguya Houraisan, a character from Imperishable Night based on a lunar princess of Japanese legend who spent a thousand years in isolation, has been depicted by the Touhou fandom as a hikikomori, a house-bound person who spends all of her time on the internet and shuns human contact. Here we have an ancient mythological character that has been repurposed for modern times, an archetype collecting dust in the cultural subconscious that suddenly has relevance and meaning again. The Japanese fans seem to treat Kaguya as a sort of household goddess, and it seems likely that the loneliness of some has been assuaged by the humor of her character.

However, the dichotomy between the characters created by Ota and the ones that emerge from the fandom’s collective dreaming can be extreme, and some fans despair that Ota’s works are dumbed down by the masses. The most notable schism lies in the fandom’s romantic imaginations, where countless pairings of the characters exist. There is practically no romance in the games, either explicit or implied, and it can be disconcerting to see how much of the fan culture is based upon these imagined relationships. American Touhou fans are often careful to distinguish between the canon mythology of the series and the one created by fans, the “fanon.” But given that Touhou is such a world unto itself, it is no surprise that the erotic and the romantic dwell there along with the spiritual and the philosophical. Every character has a different significance to every person, and the intersection of these private conceptions is realized through the public display of art: a million images of Hakurei Reimu and her cohorts are lined up alongside one another forming a digital tapestry, a whole much greater than the sum of its parts, a world woven together by the spinning threads of a million dreams.

Truly, Touhou would not be what it is without the fan culture. For many, it has become an emergent mythology: a collective, public fantasy world on a scale rarely seen outside of the major religions or other massive cultural phenomena like Star Wars. Touhou is something special because Ota has allowed it to belong to everyone who experiences it and contributes to it, just as much as it belongs to him.

The two most interesting characters Ota has created may be Maribel Hearn and Renko Usami, humans who do not live in Gensokyo and who appear only on the covers of his music compilation CDs. They are in college, Maribel a student of “relative psychology” and Renko of “super unified physics.” One believes that truth is found in the subjective, while the other worships the objective. They wear black and white hats, yin and yang, and together they form a two-person club concerned with the paranormal. Maribel, the relativist, is the one who sees Gensokyo in her dreams.

Article sources and further reading:

a Tumblr dedicated to ZUN (you can get a good sense of his character here)

Just a heads up, the touhou wiki has moved to http://touhouwiki.net . The wiki at wikia was abandoned and hijacked, and now it’s being updated in bad faith (by copying and pasting the new wiki’s own info) to make it seem like it’s still alive. Most of the info there is still outdated despite that.

More info here: http://www.shrinemaiden.org/forum/index.php/topic,7710.0.html

Could you please update that link in your post ? ^^;

I was actually aware of this wiki war situation, but I guess I forgot which one was the new official one. I still like the layout style of the old wiki, haha. I appreciate all the work you guys do, though, and I will change the link. Hope you enjoyed the article!

Excellent article! Made me want to play the game and draw some characters again~

I’d like to point out that “circle” is not the translation for “doujin” but actually in japanese “サークル”/”circle” means “club”. So I think “circle” comes from the romanisation of “club for amateurs” or “doujin circle” in japanese.

Moreover you say that ZUN made Cirno into an idiot but I remember reading that she already was an idiot in fanmade work and that ZUN liked the idea. Though I agree the meme with the ⑨ came after.

Thank you! I wrote this two years ago and it’s nice to see that it suddenly got a lot of exposure just now. Where was it linked on Facebook, just out of curiosity? I can tell the hits are coming from there, but not which page.

I don’t know Japanese so my exact translation could’ve been wrong. A “circle” and a “club” are basically the same thing though. And yeah, that’s interesting about Cirno. I know ZUN says he tries not to be influenced by the fan stuff, but with the sheer amount of it out there it must be hard not to be. I think he probably looked at it more back then.

Great article, I really enjoyed reading it. Speaking of the sheer size of the the Touhou Doujin scene, check out this article comparing the amount of Touhou fanwork compared to other popular series. http://www.japanator.com/touhou-is-way-too-popular-on-the-doujinshi-scene-14537.phtml

Note that this was written about five years ago, the numbers are certainly much, much larger by now.

Something else notable about the Touhou doujin scene is how CLEAN it is compared to others. Many other series’ doujin works have rather significant percentages of adult-only works to the total, sometimes reaching as high as 94% in some cases. Touhou, however, sits at a mere 16% adult-only works. (Although, rather humorously, due to the sheer number of Touhou fan works, that 16% is still larger than the total number of works of the second most popular series at the time, Vocaloid.)

This really speaks volumes about the Touhou community to me. Most series’ doujinshi sell for the sex and debauchery, but Touhou’s fans are truely in it for the love of the characters, and for the love of the series.

“No one shall be able to drive us from the wonderland that ZUN created for us”. — ChaosAngel, The Poltergeist Mansion

Thanks man! That article is quite interesting; I had never heard anything about the percentages of adult vs non-adult doujin, and I had no idea the numbers were that low. 16% is hardly anything! And yet it still eclipses the vocaloid ero doujin output. Hilarious. Also I laughed at “Touhou is wasting the limited resources of doujin authors.”

There really is something special about it. In the couple years after writing this I’ve become more and more convinced that the series speaks to the common religious impulse that people have. ZUN never talks about it (that I have seen), but he is clearly very well-read in spiritual literature. Maybe it comes from his family and his country upbringing. I’m a big fan of Alan Watts, who was a popularizer of eastern philosophical and spiritual ideas, and from that perspective I recognize so many genuinely enlightened things in the series… The religious references permeate the games constantly, from the conversations the characters have to the titles he chooses for the songs, but I think the most powerful indication of this is just the overall vibe and attitude on display. There’s a seriously “zen” element to Touhou. It’s honestly enlightened in some way. Completely un-neurotic. And if you look at how the guy lives, it’s more or less like an artistic monk. He doesn’t try to make a lot of money. He’s very low-key and humble. Seeing pictures and footage of him interacting with the American fans when he came to AWA amazed me… He just acted like an ordinary person, not special in any particular way. And not worried or anxious at all. When you take a personality like that and combine it with an enormous creative talent and a brilliant imagination, you end up with Touhou. I think it’s so wildly successful because it genuinely provides some kind of metaphysical meaning in people’s lives. It essentially offers the kind of escapism that you normally get with video games or anime, but escapism into a place where things are relaxing and balanced, and where there is still meaning to be found in the deep underlying mystery of the world. A place that by its very nature excites us to create and imagine; to create meaning ourselves. And that is a very powerful thing in a modern world where scientific truth and highly neurotic ideological narratives are constantly taking meaning away from us as individuals. Touhou is something that lets us take it back. I’m waiting for someone else to catch on to this phenomenon enough to write a published article about it, or maybe a book. Maybe I should do that!

Incidentally, the Summer after I wrote this article, ZUN released this album: http://en.touhouwiki.net/images/f/fa/ZCDS-0014.jpg

Look at how proud Maribel looks! I have no idea whether this is probable or not, but do you think maybe he read this and thought I was right, about her so strongly representing the shared subjectivity of the series? And that title… It was hard for me to believe it was a coincidence.

I want to meet him myself someday and ask him if he ever read this. But in any case, that made me feel like what I wrote was right on target.

Thanks again for commenting!

Being a native Atlantan, I actually met him at AWA last year. He was… shorter than I expected.

Did you talk to him? What was the experience like?

This made me cry.

I cry at the feeling that I still love this series, but I may not like as much as I did one day.

The days I had a fiery passion for all this work, those were the days.

Wow, thank you! I’m touched that my writing was able to invoke that kind of a reaction in someone.

I think your love for the series now is enough. It was enough for you to cry. 🙂 There is a time for everything in life, and if we always felt the same way about things then we wouldn’t be living human beings. And there’s something beautiful about what you’re feeling, about having that bittersweet nostalgia for the past. It’s very “Yūgen.” The Portugese also call it “Saudade.” 🙂

Check this out! https://gnosisonic.wordpress.com/2011/01/13/yugen-in-the-nature-art-of-touhou/

Gosh, that production point, gosh he is feeling just like me.